Country Selector

Please enter a valid location

2026 planting weather outlook

How quickly La Niña transitions into neutral will shape the spring forecast — for better or worse.

The front-loaded early winter of snow and cold occurred as predicted, thanks to a La Niña that peaked in December. But planting season weather will depend on how and when the neutral phase locks in.

“Current models insist on a neutral weather phase arrival by the end of winter or the warm side of neutral during spring, which could cause all kinds of havoc,” said John Baranick, DTN Ag meteorologist.

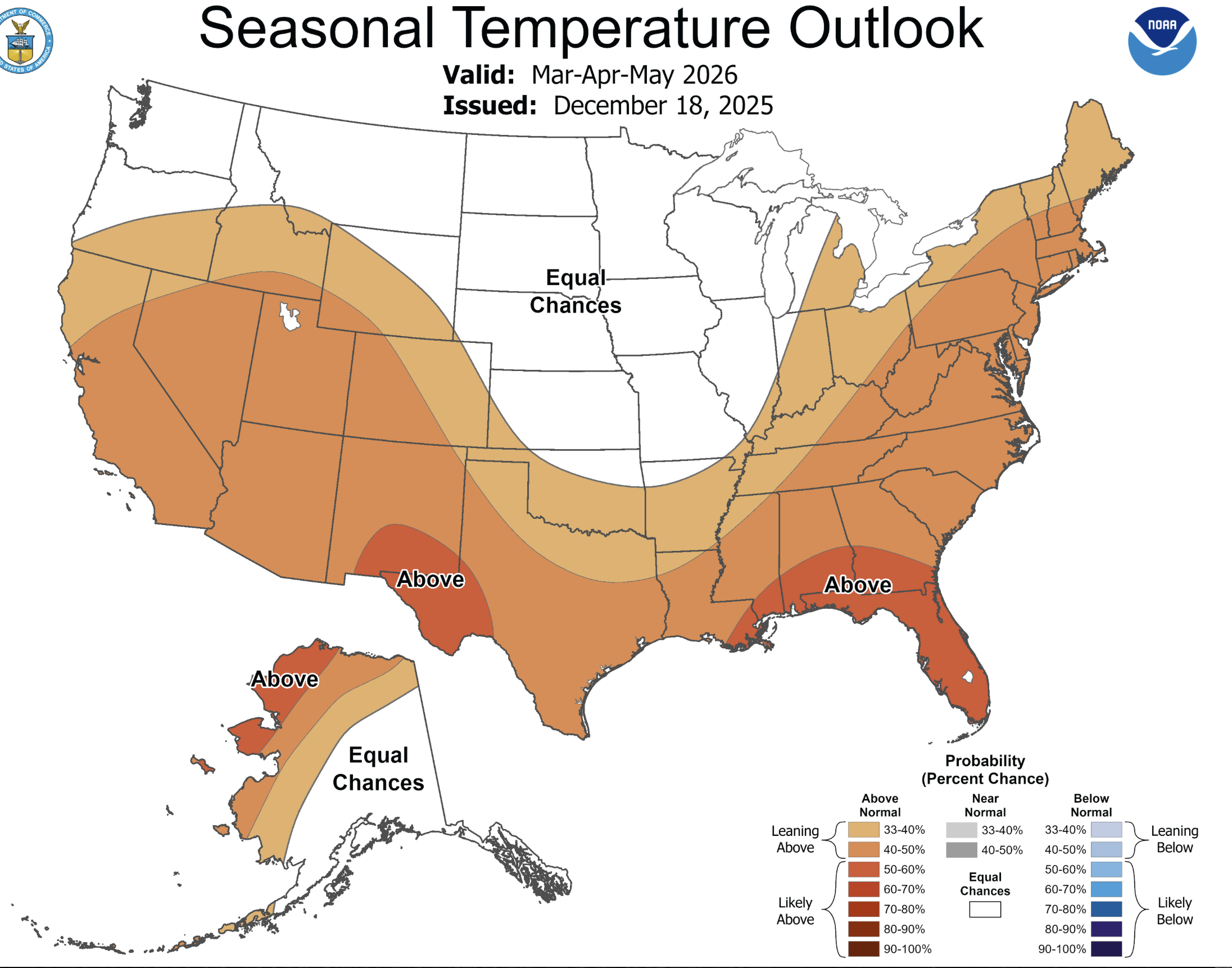

As February arrives, models show, shifting wind patterns won’t push all this cold air through the United States. Baranick said DTN is currently forecasting colder conditions in the Northwest and a warmer Southeast. Yet, these competing movements will battle throughout February and March.

“This means that a lot of the Corn Belt will receive decent precipitation in February and March, along with a possible early start to severe weather season in the southern Plains,” Baranick said. “The prediction challenge lies in how fast or slow La Niña fades into neutral.”

As of early January, Baranick predicted a typical, slower-fading La Niña, meaning winter hangs on. It will bring colder air and frost potential through April, especially across the northern Corn Belt. However, a faster-fading La Niña could flip that script, bringing warmer air for the planting season, with trends toward El Niño this summer.

Drought relief

Corn Belt areas with the deepest drought — central Illinois through northern Indiana and northwestern Ohio — are forecast to receive significant rainfall to reverse much of the area’s drought.

“The possibility of late planting due to soggy soil may occur from Missouri up through Michigan and farther south through the Ohio Valley into the Tennessee Valley,” Baranick said. “The predicted snowpack buildup across the Dakotas, Minnesota, Iowa and Wisconsin could take a long time to melt and delay planting.”

Although this spring shows a better chance of widespread planting delays, the sweet spot area for timely planting appears to be in Nebraska, Kansas and Missouri.

The only drought areas Baranick is concerned about are outside the Corn Belt, such as the wheat areas of Montana, across Southeastern cotton and peanut acres, and into Texas and the interior western United States.

With a possible shift toward El Niño during the second half of spring, a weather pattern with greater temperature and precipitation variability across the Corn Belt can occur. Baranick remained hopeful for these drier stretches to get fieldwork done, along with plenty of rain, so soils don’t dry out too much. Such a pattern also delivers temperatures that never get too cold or too hot for very long.

“Nothing really points to a hot and dry summer, nor do we see any huge issues during the beginning of the growing season,” Baranick said. “Honestly, it looks like a pretty decent growing season in 2026, especially if we do head into El Niño territory. That will deliver a variable and active weather pattern that is a good thing for U.S. farmers.”

A hot topic on farmers’ minds is whether the yield-stealing southern rust will ride weather patterns from the South into the Corn Belt during 2026. “The wet spring across the South, combined with a wet Corn Belt through the first half of summer last year, set up the perfect storm for southern rust to invade fields,” Baranick explained. “Unfortunately, our current forecast for another wet spring across the South and the Corn Belt could be setting us up for another year of southern rust,” he said.

Global weather concerns

Early weather concerns that cropped up in South America have since subsided. Argentina and southern Brazil are receiving enough rainfall to maintain the growing crop. Central Brazil was drier for the first two crop months, but November and December rains set soybean pods nicely.

Baranick said Europe is in good shape, having overcome early dry periods like South America has. In the Black Sea region, satellite imagery suggests potential dryness in eastern Ukraine and southwestern Russia. “They haven’t had much precipitation, but our usually reliable SovEcon source says things are going well there,” he added.

In the corn and soybean areas of central and northeastern China, they received good moisture to end the season, so they should be fine this spring. The same outlook exists for South Africa’s corn areas.

“Overall, there are not many global troubled weather spots right now that could boost U.S. grain prices and exports,” Baranick said. “But potential for below-normal precipitation for much of South America going forward could cause issues for their safrinha (second) crops.”

More information:

- Weekly Weather and Crop Bulletin https://www.usda.gov/sites/default/files/documents/wwcb.pdf

- Midwest drought monitor map https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/CurrentMap/StateDroughtMonitor.aspx?midwest

- High Plains drought monitor map https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/CurrentMap/StateDroughtMonitor.aspx?high_plains

- Soil moisture outlook https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/Soilmst_Monitoring/US/Soilmst/Soilmst.shtml

- DTN Ag Weather Forum https://www.dtnpf.com/agriculture/web/ag/blogs/ag-weather-forum

Content provided by DTN/The Progressive Farmer

The More You Grow

Find expert insights on agronomics, crop protection, farm operations and more.